Recently I rode the Manitou and Pike’s Peak Cog Railway to the top of the mountain that Zebulon M. Pike didn’t summit on his 1806 expedition – although it bears his name. It was a chilly, overcast late winter/early spring day as we rode in cozy comfort up the 25 percent grade to reach the top in only an hour and a half.

The view – even on a gray and windy day – is spectacular. It was easy to see why, in 1806, Zebulon Pike set his sights on this peak as the perfect platform from which to survey the broad plains stretching below the Front Range. The easternmost of the “fourteeners” (mountain peaks more than 14,000 feet high) in Colorado, Pikes Peak commands the Front Range. Today it is known as “America’s Mountain”, inspiration for the song “America the Beautiful”, and the destination for gold-seeking settlers of the mid-nineteenth century with the mantra of “Pike’s Peak or Bust!”

But Pike never made the summit.

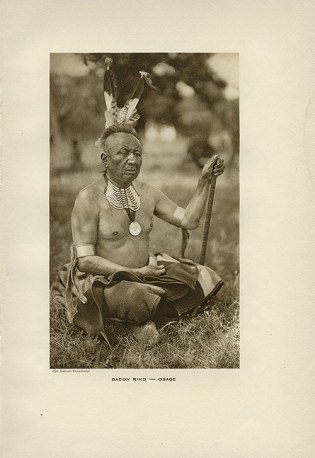

He and his expedition left St. Louis in July 1806, to document the southern portions of the new Louisiana Purchase and find the source of the Red River. His first mission, however, was to return to their families forty-six Osage women and children who had been kidnapped by Potawatomi raiding parties in 1803 and ransomed by the U.S. To achieve this grand gesture, the party trekked up the Missouri River to the Osage River and continued west to Osage villages near what is now the Kansas state line. “Sans Oreilles (No-Ears), one of the (Osage) chiefs who had returned from Washington made a flattering speech: ‘Osages, you now see your wives, your brothers, your daughters, your sons, redeemed from captivity. Who did this? Was it the Spaniards? No. The French? … The Americans stretched forth their hands and they are returned to you!'” (Damming the Osage, page 35, 36)

The town of Butler, Missouri, commemorates the ceremonial meeting in a mural on the town square.

“Zebulon Pike Parley with Osage Chief” – mural by Dan Brewer, Butler, Missouri

Mural by Dan Brewer, Butler, Missouri – seat of Bates Count

Zebulon Pike mural in Butler, Missouri

With that auspicious first goal successfully achieved, Pike and his expedition continued across the great Plains through the summer, making the Front Range in November, just as winter was setting in. Almost unfazed by the “Grand Peak,” Zebulon Pike tried to climb it with a few ill-equipped men and no supplies. Realism inspired by lack of game for food and meteorological challenges overcame ambition. Pike chose to quit the endeavor:

“…here we found the snow middle deep; no sign of beast or bird inhabiting this region. The thermometer which stood at 9° above 0 at the foot of the mountain, here fell to 4° below 0. The summit of the Grand Peak, which was entirely bare of vegetation and covered with snow, now appeared at the distance of 15 or 16 miles (24 or 26 km) from us, and as high again as what we had ascended, and would have taken a whole day’s march to have arrived at its base, when I believed no human being could have ascended to its pinical [sic]. This with the condition of my soldiers who had only light overalls on, and no stockings, and every way ill provided to endure the inclemency of the region; the bad prospect of killing any thing to subsist on, with the further detention of two or three days, which it must occasion, determined us to return.”

He and his men did not return – but his name and the commanding view he sought remain.

When we published this photograph of Osage Chief Red Eagle’s Wife and Daughter we speculated that the Chief referred to was Paul Red Eagle. Recently Michael Snyder, author of a soon-to-be-released biography of John Joseph Mathews set us straight.

When we published this photograph of Osage Chief Red Eagle’s Wife and Daughter we speculated that the Chief referred to was Paul Red Eagle. Recently Michael Snyder, author of a soon-to-be-released biography of John Joseph Mathews set us straight.